Religious practices in ancient China go back over 7,000 years. Long before the philosophical and spiritual teachings of Confucius and Lao-Tzu developed or before the teachings of the Buddha came to China, the people worshipped personifications of nature and then of concepts like "wealth" or "fortune" which developed into a religion.

These beliefs still influence religious practices today. For example, the Tao te Ching of Taoism maintains that there is a universal force known as the Tao which flows through all things and binds all things but makes no mention of specific gods to be worshipped; still, modern Taoists in China (and elsewhere) worship many gods at private altars and in public ceremonies which originated in the country's ancient past.

Scholar Harold M. Tanner writes, "The gods, spirits, and ancestors could affect crops, the weather, childbirth, the king's health, warfare, and so on. It was, therefore, important to sacrifice to them" (43). The gods grew out of people's observance of natural phenomena which either frightened them and caused uncertainty or assured them of a benevolent world, which would protect them and help them succeed. As time passed, these beliefs became standardized and the gods were given names and personalities, and rituals developed to honor the deities. All of these practices were eventually standardized as "religion" in China just as similar beliefs and rituals were everywhere else in the ancient world.

Early Evidence of Religious Practice

In China, religious beliefs are evident in the Yangshao Culture of the Yellow River Valley, which prospered between 5000-3000 BCE. At the Neolithic site of Banpo Village in modern Shaanxi Province (dated to between c. 4500-3750 BCE) 250 tombs were found containing grave goods, which point to a belief in life after death. There is also a ritualistic pattern to how the dead were buried with tombs oriented west to east to symbolize death and rebirth. Grave goods provide evidence of specific people in the village who acted as priests and presided over some kind of divination and religious observance.

The Yangshao Culture was matrilineal, meaning women were dominant, so this religious figure would have been a woman based on the grave goods found. There is no evidence of any high-ranking males in the burials but a significant amount of females. Scholars believe that the early religious practices were also matrilineal and most likely animistic, where people worship personifications of nature, and usually feminine deities were benevolent and male deities malevolent, or at least more to be feared.

These practices continued with the Qijia Culture (c. 2200-1600 BCE) who inhabited the Upper Yellow River Valley but whose culture could have been patriarchal. Examinations of the Bronze Age site of Lajia Village in modern-day Qinghai Province (and elsewhere) have uncovered evidence of religious practices. Lajia Village is often referred to as the "Chinese Pompeii" because it was destroyed by an earthquake which caused a flood and the resulting mudslides buried the village intact.

Among the artifacts uncovered was a bowl of noodles which scientists have examined and believe to be the oldest noodles in the world and precursors to China's staple dish "Long-Life Noodles". Even though not all scholars or archaeologists agree on China as the creator of the noodle, the finds at Lajia support the claim of religious practices there as early as c. 2200 BCE. There is evidence that the people worshipped a supreme god who was king of many other lesser deities.

Ghosts & Religion

By the time of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) these religious beliefs had developed so that now there was a definite "king of the gods" named Shangti and many lesser gods of other names. Shangti presided over all the important matters of state and was a very busy god. He was rarely sacrificed to because people were encouraged not to bother him with their problems. Ancestor worship may have begun at this time but, more likely, started much earlier.

Evidence of a strong belief in ghosts, in the form of amulets and charms, goes back to at least the Shang Dynasty and ghost stories are among the earliest form of Chinese literature. Ghosts (known as guei or kuei) were the spirits of deceased persons who had not been buried correctly with due honors or were still attached to the earth for other reasons. They were called by a number of names but in one form, jiangshi ("stiff body"), they appear as zombies.

Ghosts played a very important role in Chinese religion and culture and still do. The ritual still practiced in China today known as Tomb Sweeping Day (usually around 4 April) is observed to honor the dead and make sure they are happy in the afterlife. If they are not, they are thought to return to haunt the living. The Chinese visit the graves of their ancestors on Tomb Sweeping Day during the Festival of Qingming, even if they never do at any other time of the year, to tend the graves and pay their respects.

When someone died naturally or was buried with the proper honors, there was no fear of them returning as a ghost. The Chinese believed that, if the person had lived a good life, they went to live with the gods after death. These spirits of one's ancestors were prayed to so they could approach Shangti with the problems and praise of those on earth. Tanner writes:

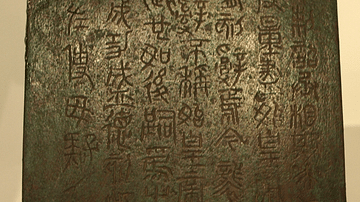

Ancestors were represented by a physical symbol such as a spirit tablet engraved or painted with the ancestor's honorific name. Rituals were held to honor these ancestors, and sacrifices of millet ale, cattle, dogs, sheep, and humans were offered. The scale of the sacrifices varied, but at important rituals, hundreds of animals and/or human sacrifices would be slaughtered. Believing that the spirits of the dead continued to exist and to take an interest in the world of the living, the Shang elite buried their dead in elaborate and well-furnished tombs. (43)

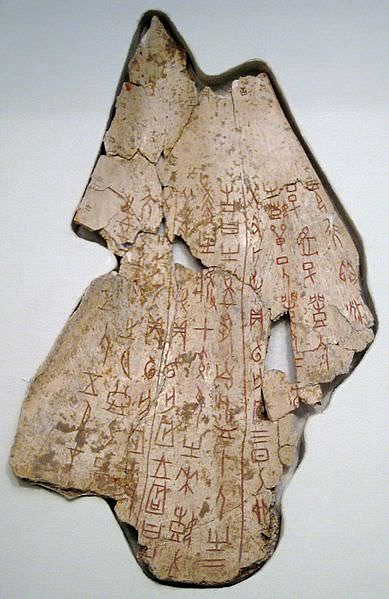

The spirits of these ancestors could help a person in life by revealing the future to them. Divination became a significant part of Chinese religious beliefs and was performed by people with mystical powers (what one would call a "psychic" in the modern day) one would pay to tell one's future through oracle bones. It is through these oracle bones that writing developed in China. The mystic would write the question on the shoulder bone of an ox or turtle shell and apply heat until it cracked; whichever way the crack went would determine the answer. It was not the mystic or the bone which gave the answer but one's ancestors who the mystic communed with. These ancestors were in touch with eternal spirits, the gods, who controlled and maintained the universe.

The Gods

There were over 200 gods in the Chinese pantheon whose names were recorded during and after the Shang Dynasty. The early gods, before Shangti, were spirits of a place known as Tudi Gong ("Lord of the Place" or "Earth God"). These were earth spirits who inhabited a specific place and only had power in that locale. The Tudi Gong were sometimes thought to be an important member of the community who had died but remained in spirit as a guardian but, more often, they were ancient spirits who inhabited a certain area of land. These spirits were helpful if people acknowledged and honored them, and vengeful if they were ignored or neglected. The Chinese concept of Feng Shui comes from the belief in the Tudi Gong.

These local earth spirits continued to be venerated even after gods developed who were more universal. One of the first deities acknowledged who probably began as a local spirit was the dragon. The dragon is one of the oldest gods of China. Dragon images have been found on the Neolithic pottery at Banpo Village and other sites. The Dragon King known as Yinglong was god of rain, both gentle rain for the crops and terrible storms, also as Lord of the Sea and protector of heroes, kings, and those who fought for right. Dragon statuary and imagery is routinely used in Chinese art and architecture to symbolize protection and success.

Some form of Nuwa, goddess of humankind, existed as early as the Shang Dynasty. Nuwa was a goddess part woman and part dragon who molded human beings from the mud of the Yellow River and blew her breath into them to bring them to life.

She continued making people and bringing them to life over and over again but grew tired of it finally and invented marriage so people could reproduce without her. She saw that people did not know how to do anything, though, so she asked her friend Fuxi for help.

Fuxi is the god of fire and the teacher of human beings. He brought fire to people and taught them how to control it to cook food, bring light, and keep warm. Fuxi also wove the first fishing nets for the people and taught them how to get food from the sea. Once their basic needs were taken care of, he gave them the gifts of music, writing, and divination. Nuwa and Fuxi were considered the mother and father of human beings and always were called on for protection.

Sun Wukong was the monkey god of mischief who caused so much trouble he was killed by the other gods and sent to the underworld. Once he got there, he erased his name from the book of the king of the underworld and not only came back to life but could never die again. His name did not develop until later but a mischevious monkey god appears on bronze inscriptions from the Shang Dynasty who appears to be this same deity.

Lei Shen was the god of thunder who was very unpleasant and beat on a large drum with a hammer whenever he became irritated. He could not tolerate anyone who wasted food and would hurl thunderbolts at them, killing them instantly. One time, he saw a woman who seemed about to throw out a bowl of rice and killed her with his thunderbolt. The gods determined that he had acted too quickly and so the woman, Dian Mu, was raised from death and became the goddess of lightning. She would flash her light to show Lei Shen where he should throw his thunderbolts so he would not make the same mistake again.

Above these gods and all the others was Shangti, the god of law, order, justice, and life known as "The Lord on High". Shangti decreed how the universe would run and the lives of all the people were under his constant watch. He was especially mindful of those who ruled over others and decided who should rule, how long, and who should succeed them.

Worship & Clergy

Chinese temples and shrines were cared for by priests and monks who were always male. Women were allowed to enter monasteries to devote themselves to the work of the gods but could not hold spiritual authority over men. Different types of religious services were held in temples for different religious beliefs. These services all had in common the sound of music, most often bells. The monastic prayers were said three times a day, at morning, noon, and night, to the sound of a small bell. Incense was burned regularly at services to cleanse the place of evil spirits and negative energies.

An important aspect of Chinese religion, whether Taoism, Confucianism, or Buddhism, was known as "hygiene schools" which instructed people on how to take care of themselves to live longer lives or even achieve immortality. Hygiene schools were part of the temple or monastery. The priests taught people how to eat healthy, exercise (the practice of Tai Chi developed through these schools), and perform rituals honoring the gods so the gods would bless them with a healthy long life.

Further Religious Developments

In the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046-226 BCE) the concept of the Mandate of Heaven was developed. The Mandate of Heaven was the belief that Shangti ordained a certain emperor or dynasty to rule and allowed them to rule as long as they pleased him. When the rulers were no longer taking care of the people responsibly, they were said to have lost the Mandate of Heaven and were replaced by another. Modern scholars have seen this simply as a justification for changing a regime but the people at the time believed in the concept.

The gods were thought to watch over the people and would pay special attention to the emperor. People continued a practice, which began toward the end of the Shang Dynasty, of wearing charms and amulets of their god of choice or their ancestors for protection or in the hope of blessings, and the emperor did this as well. Religious practices changed during the latter part of the Zhou Dynasty owing to its decline and eventual fall but the practice of wearing religious jewelry continued.

The Zhou Dynasty is divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771-226 BCE). Chinese culture and religious practices flourished during the Western Zhou period but began to break apart during the Eastern Zhou. Religious practices of divination, ancestor worship, and veneration for the gods continued, but during the Spring and Autumn Period (772-476 BCE) philosophical ideas began to challenge the ancient beliefs.

Confucius (l. c. 551-479 BCE) encouraged ancestor worship as a way of remembering and honoring one's past but emphasized people's individual responsibility in making choices and criticized an over-reliance on supernatural powers. Mencius (l. c. 372-289 BCE) developed the ideas of Confucius, and his work resulted in a more rational and restrained view of the world. The work of Lao-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) and the development of Taoism might be seen as a reaction to Confucian principles if not for the fact that Taoism developed many centuries before the traditonal date assigned to Lao-Tzu. It is much more probable that Taoism developed from the original nature/folk religion of the people of China than that it was created by a 6th-century BCE philosopher. Therefore, it is more accurate to say that the rationalism of Confucianism probably developed as a reaction to the emotionalism and spiritualism of those earlier beliefs.

Religious beliefs developed further during the next period in China's history, The Warring States Period (476-221 BCE), which was very chaotic. The seven states of China were all independent now that the Zhou had lost the Mandate of Heaven, and each one fought the others for control of the country. Confucianism was the most popular belief during this time, but there was another which was growing stronger. A statesman named Shang Yang (d. 338 BCE) from the region of Qin developed a philosophy called Legalism which maintained that people were only motivated by self-interest, were inherently evil, and had to be controlled by law. Shang Yang's philosophy helped the State of Qin overpower the six other states and the Qin Dynasty was founded by the first emperor, Shi Huangti, in 221 BCE.

Religion Banned and Revived

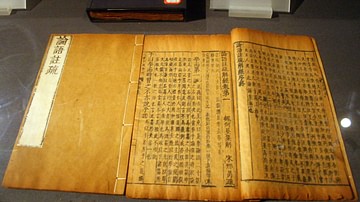

During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), Shi Huangti banned religion and burned philosophical and religious works. Legalism became the official philosophy of the Qin government and the people were subject to harsh penalties for breaking even minor laws. Shi Huangti outlawed any books which did not deal with his family line, his dynasty, or Legalism, even though he was personally obsessed with immortality and the afterlife, and his private library was full of books on these subjects. Confucian scholars hid books as best as they could and people would worship their gods in secret but were no longer allowed to carry amulets or wear religious charms.

Shi Huangti died in 210 BCE while searching for immortality on a tour through his kingdom. The Qin Dynasty fell soon after, in 206 BCE, and the Han Dynasty took its place. The Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) at first continued the policy of Legalism but abandoned it under Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BCE). Confucianism became the state religion and grew more and more popular even though other religions, like Taoism, were also practiced.

During the Han Dynasty, the emperor became distinctly identified as the mediator between the gods and the people. The position of the emperor had been seen as linked to the gods through the Mandate of Heaven from the early Zhou Dynasty but now it was his express responsibility to behave so that heaven would bless the people. Mount Tai became an important sacred site during this time and ancient rituals and festivals were revised. An example of this would be the Festival of the Five Elements which honored earth, fire, metal, water, and wood which was changed to the Festival of Heaven and Earth, honoring the people's relationship with the gods.

An important religious sect which gained popularity during this time was the cult of the Queen Mother of the West, Xi Wang Mu, goddess of immortality. She lived in the mountains of Kunlun, like the other gods, but in a castle of gold, with a moat around it, so sensitive that anything, even a hair, which fell upon it would sink. She walked every day in her Imperial Peach Orchard whose fruit held the divine juices of immortality. Scholar Patricia Buckley Ebrey comments on this cult:

During the Han period, the hope for deathlessness or immortality found expression in the cult of a goddess called the Queen Mother of the West. Her paradise was portrayed as a land of marvels where trees of deathlessness grew and rivers of immortality flowed...People of all social levels expressed their devotion to her, and shrines were erected under government sponsorship throughout the country. (71)

The Queen Mother of the West was sometimes represented as an old, unattractive woman with sharp teeth like a tiger's and a hunched back, and at other times as a beautiful woman with long hair. She jealously guarded the secrets of immortality in her garden and struck down people who tried to find their way in. She was kind to her followers, though, and blessed them as long as they pleased her.

The Arrival of Buddhism

In the 1st century CE, Buddhism arrived in China via trade through the Silk Road. According to the legend, the Han emperor Ming (r. 28-75 CE) had a vision of a golden god flying through the air and asked his secretary who that could be. The assistant told him he had heard of a god in India who shone like the sun and flew in the air, and so Ming sent emissaries to bring Buddhist teachings to China. Buddhism quickly combined with the earlier folk religion and incorporated ancestor worship and veneration of Buddha as a god.

Buddhism was welcomed in China and took its place alongside Confucianism, Taoism, and the blended folk religion as a major influence on the spiritual lives of the people. When the Han Dynasty fell, China entered a period known as The Three Kingdoms (220-263 CE) which was similar to the Warring States Period in bloodshed, violence, and disorder. The brutality and uncertainty of the period influenced Buddhism in China which struggled to meet the spiritual needs of the people at the time by developing rituals and practices of transcendence. The Buddhist schools of Ch'an (better known as Zen), Pure Land, and others took on form at this time.

Buddhism introduced a new kind of ghost to China, the egui ("Hungry Ghost"), which became one of the most feared. The modern day Ghost Festival in China (also known as the Hungry Ghost Festival) grew out of this belief. Hungry ghosts were spirits of those who had been murdered, improperly buried, or had sinned and not been forgiven. They could also be people who had never been satisfied with anything in life and were no happier in death. People would leave food out for them during Ghost Month to appease them and went to the graves of their ancestors to sacrifice food so they would not become hungry ghosts.

The Tang Dynasty & Religion in China

The major religious influences on Chinese culture were in place by the time of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) but there were more to come. The second emperor, Taizong (626-649 CE), was a Buddhist who believed in toleration of other faiths and allowed Manichaeism, Christianity, and others to set up communities of faith in China. His successor, Wu Zeitian (r. 690-704 CE), elevated Buddhism and presented herself as a Maitreya (a future Buddha) while her successor, Xuanzong (r. 712-756 CE), rejected Buddhism as divisive and made Taoism the state religion.

Although Xuanzong allowed and encouraged all faiths to practice in the country, by 817 CE Buddhism was condemned as a dividing force which undermined traditional values. Between 842-845 CE Buddhist nuns and priests were persecuted and murdered and temples were closed. Any religion other than Taoism was prohibited, and persecutions affected communities of Jews, Christians, and any other faith. The emperor Xuanzong II (r. 846-859 CE) ended these persecutions and restored religious tolerance. The dynasties which followed the Tang up to the present day all had their own experiences with the development of religion and the benefits and drawbacks which come with it, but the basic form of what they dealt with was in place by the end of the Tang Dynasty.

Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and the early folk religion combined to form the basis of Chinese culture. Other religions have added their own influences but these four belief structures had the most impact on the country and the culture. Religious beliefs have always been very important to the Chinese people even though the People's Republic of China originally outlawed religion when it took power in 1949 CE.

The People's Republic saw religion as unnecessary and divisive, and during the Cultural Revolution temples were destroyed, churches burned, or converted to secular uses. In the 1970's CE the People's Republic relaxed its stand on religion and since then has worked to encourage organized religion as "psychologically hygienic" and a stabilizing influence in the lives of its citizens.